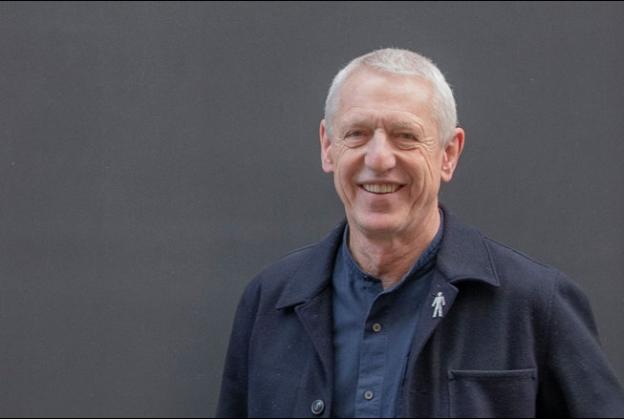

Raj Patel, Fellow - Arup

While barely needing an introduction, Arup provides international planning, engineering, design and consulting services for some of the most prominent projects and sites anywhere in the built environment. Arup Fellow and world leader in the field of acoustic design, Raj Patel credits working for the practice since 1993 with ‘freedom for boundless creativity. Resources to achieve what seems impossible. Working with the best people in the world to do it’.

A staunch proponent of the importance of getting the acoustics right as part of the architectural process, Raj, spearheaded the creation of SoundLab®, since used around the globe on high-profile projects. These include music venues in challenging urban environments, such as Brooklyn Steel and Sawdust in NYC, which we discuss with him.

A life-long musician himself, Raj lets us in on some of his current musical influences. But first; how it all started with a whistle…

We’re curious about how the simple act of whistling and its vibrational effect on space has inspired your thinking ever since you were a child? What brought that about?

One of my first experiences of architecture and sound influencing each other was a long, narrow, tall alleyway that led to my house from the street. It was brick and plaster. As soon as you were a few steps into it the sound of the environment changed, and manipulating it, with whistling, claps and foot stamping was dramatic. The ability to manipulate sound and space fascinated me from that moment and has stayed with me ever since

Although you are now a world-renowned acoustic architect, you originally trained as a musician, graduating from a drum kit aged 3, trumpet at age 10, to electric bass at 14. It strikes us that the thing that underpins and breathes life into both music and art is mathematics, so what do you think is the magic equation between sound and architecture?

The equation is not magic, it is intrinsic. When we are born, we can hear a range of sounds from 20Hz at low frequency to 20,000 Hz at high frequency (to put into context the keys on a piano keyboard go from approximately 27Hz at the lowest key, to 4000Hz at the top). The wavelength of sound at 20Hz is ~17m, at 20,000Hz is 17mm, so across our range of hearing, architecture and architectural finishes are scaled to wavelength. If you want to shape sound at a particular frequency, the large-scale room dimensions influence low and mid-frequencies, detailing influences mid and high frequencies, and material selection influences the sound absorbing, reflecting, and diffusing qualities. Our ears are on the side of our head, designed to work 24/7/365 and compensate for what our eyes cannot do – it is very easy to trick the eye, and very hard to trick the ear. Listening is a 3D activity, so crafting how sound reaches listeners in 3D is important. To craft architecture for sound, you need to understand what a space will be used for, then optimize shape, form, volume and material distribution to deliver that experience. The equation is finely balanced. Get it right and it can be perfect, get one or two factors off, and it can be immediately noticeable, even to the untrained ear.

You went on to study engineering acoustics and vibration at the University of Southampton. How did you then come to work for Arup?

One of my classmates was sponsored by Arup and interned there, so I knew about the work they were doing from her. When University was over, I was working for a small consulting firm in Lewes in East Sussex. My classmate was working for Arup on Glyndeborne Opera House. A contractor needed some testing done on the performance of some acoustic elements, which Arup were to witness, so she referred them to me. I spent a week working at Glyndebourne doing the testing and reporting to the Arup team, which effectively turned into a week-long interview. After that was completed, I had a formal interview and within a couple of weeks was working for Arup; that was in December 1993.

Can you tell us the story behind the creation of SoundLab, a ground-breaking resource for creating accurate audio renderings of 3D space, which you helped pioneer in Arup’s New York offices over 20 years ago?

It didn’t take long to realise that reporting advice on acoustics in words, reports, sketches, diagrams and computer models, often made it hard to get your point across, especially to architects. Some followed advice based on trust alone. Others were very resistant. As already mentioned, when everything about the architecture – shape, form, material selection, construction - all impact the acoustic outcome, you need architects and engineers to integrate your requirements into the fundamentals of their design.

It was clear this would be much more effective if we had a workflow that could do that all by using sound. That was the genesis of the concept. We had to bring together a range of tools, techniques and processes to make it happen, but most importantly we needed to be able to do it on desktop computers with reasonable processing time to enable it to happen on all projects. That inflection point came about in 1996, when we did our first successful experiments, and we accelerated from there.

Today, SoundLab is used in Arup’s offices around the world. How influential do you feel SoundLab has been in harmonising the ‘invisible art’ of acoustics and the very visual art of architecture? And what can and does go wrong without that vital interplay?

I think it has had a profound impact and will continue to do so. It enables clients, designers and other project constituents to come together in a way that was not possible before. You can look at and hear architecture, and with VR you can also integrate it together with a full immersive visualisation. It helps foster integrated thinking and design, and also a much deeper appreciation and mutual respect for what you are trying to achieve from the design. And of course, when a client sees a VE (Value Engineering) item with the word "acoustics" next to it , they remember the SoundLab experience and why they need to keep those things in, and what will go wrong if they don’t.

In 2020, your book ‘Architectural Acoustics: A guide to integrated thinking’ was published worldwide by the Royal Institute of British Architects. The book draws on your own experiences of how well-considered acoustics can bring an added dimension to projects, and gives many case studies. What are some of your personal favourites?

There are so many, it’s hard to know where to start. Jubilee Line Extension in the UK, the line I used to live on for most of my childhood, is a standout. I worked on every station on the line to develop not only exceptionally well-designed acoustic spaces, but also to enable an excellent user experience with clear, intelligible PA messages.

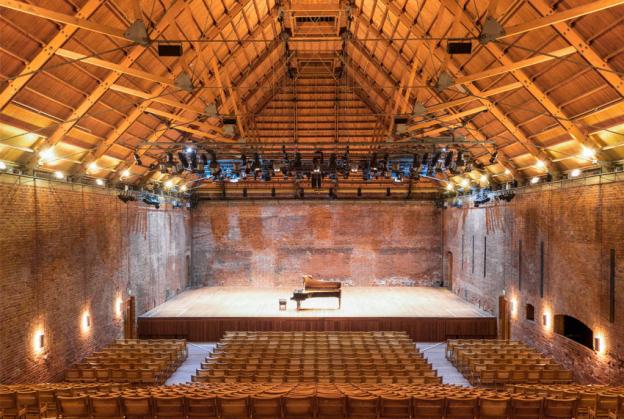

Then there’s Snape Maltings Refurbishment. A landmark and well-renowned space, it is also a naturally ventilated concert hall which is both rare and far ahead of its time. It was a landmark project for Arup, and the refurbishment process sought to preserve all of that, but also give it a new lease of life moving into the 21st century. As well as the design, I worked in an advisory capacity to help develop a deal between a major record company to start recording there again, which helped secure the funding needed to allow the project to progress.

In Brooklyn, both National Sawdust and Brooklyn Steel are two buildings close to my heart. I led the design of both, and have the joy of being able to see performers and audiences enjoy them, and it helps my children understand what I do.

Starting with one of those favourites, the Brooklyn Steel project in Brooklyn, NY, your biggest challenge lay literally over the street in the form of a dense public housing project. Converting an old steel works into an 1800-capacity amplified music venue for The Bowery Presents, and having to meet the strict noise emission standards set by the New York City Noise Code must have been interesting! How did you achieve keeping the neighbours happy but keeping the full acoustic impact for audiences?

Yes, it was a challenge! Resolution involved two essential components: an engaged pro-active client always striving for excellence and secondly, holistic project thinking. The need to meet the Noise Code was a given. We were dealing with adaptive reuse of an existing structure. The old steel works had a lot to offer in this regard as we considered its conversion to an amplified music venue. The existing roof could not take significantly more weight, and creating more internal structures to minimise sound emission would have reduced the venue capacity, which was not desired. Our client, The Bowery Presents has always had a strong focus on the quality of sound in their venues, seeking to offer audience and performers the best experience possible. So, we employed a two-fold strategy.

First, was to ensure that the interior acoustics of the venue were excellent – by absorbing as much sound as possible across the amplified music frequency range as practical, while still allowing some room response so that it retains excitement for the audience. Various thicknesses from 50mm to 200mm of raw sound absorbing material with black tissue facing was used. Lightweight sprayed material to the roof served both as sound absorber and fire protection. Collectively, this had an important operational influence because when room acoustics are poor, the sound crew often push the volume up to compensate as best they can, usually resulting in more problems. Here, the sound is clear and impactful, so they don’t have to drive the room as hard.

Knowing that outcome was in hand allowed the next step to be very precise. We analysed the sound insulation performance of all the external facing façades and roof and the impact of sound from these individually and collectively to the neighbours. The roof was the weakest performing element and net overall main contributor, as the surrounding buildings look down onto it. From that perspective, seeing the whole roof is like looking directly at a loudspeaker sending sound to you. The roof could take very little weight internally. The limited capacity that was available was at the roof perimeter. So, we designed a specialised green roof supported around the perimeter, where the height and contained volume was optimised and tuned to absorb sound. I’m pleased to say the overall result has been very successful.

Moving on to National Sawdust, also in Brooklyn, where Arup provided acoustic, audio-visual, theatre and lighting consultancy, and design services. A former warehouse now provides 24/7 space to nurture new talent, compose, perform, and record. SoundLab played a vital role in designing its outstanding, and flexible, acoustics. Can you explain what it was used for and how it contributed?

The project started with blank page. The client had high aspirations for creating a new kind of venue - to have a broad reach - and to be progressive, which they articulated to us. The only “constraint” was that ideally the project would fit into one or more standard lot sizes in the Williamsburg neighbourhood in Brooklyn. We worked with the architects Bureau V to develop the design and programming, floor plans and layouts, and to develop a cost estimate. We spent a lot of time in the Arup SoundLab® in this early phase - listening to different room shapes, forms and geometries, and to different kinds of music - to all agree on the final approach for that critical part of the design. Once that was done, the next step was to find a site, in a place that was undergoing transformative change.

Having eventually found the right place, the main challenge of the site was the close proximity to the L subway train, which creates a lot of vibration and structure-borne noise. For this venue, which hosts very sensitive performances and sound recordings, we needed to be free from intrusive noise. Within the week, we had conducted a survey and quantified the impact of the subway. SoundLab was used to listen to the level of anticipated subway noise under each condition. We agreed on an approach to deal with it, involving floating the venue and additional recording spaces on springs, and the springs absorb the vibration to limit how much gets into the structure.

The SoundLab was also used to listen to the venue in different operational modes throughout the design, to different music types, and in developing the final design approach. This consists of an acoustically transparent metal lattice interior and in the void, between that and the wall, sound absorbing curtains which can be opened and moved to adjust the room acoustics based on the performance type.

On the Western Seaboard of the USA, is one of the country’s largest museums of modern and contemporary art, the San Francisco MOMA (SFMOMA). Arup provided integrated room acoustics and flexible audio-visual infrastructure design. SFMOMA has very diverse curational needs, so how did the teamwork to meet those needs?

We also provided lighting and façade design for the building. When you consider all these disciplines together there is a very high level of curatorial engagement required to satisfy the building needs, and they touch every aspect of the operational and performance needs of exhibitions. Our façades and lighting teams worked very closely with the curatorial team (and architects Snøhetta) in determining performance criteria for daylighting and electric lighting requirements in the gallery spaces and then working to develop the aesthetic and design approaches to delivery. There are a variety of environments within the space, allowing works to be showcased in different ways.

It is common for elements of acoustics, audio-visual, lighting, and other technologies to get moved from being part of design to “procure later” or to “FF&E” in building design processes – because these elements are less tangible to all members of the design team, unlike, for example, deciding to eliminate all the doors, the impact of which is more obvious. But we know from our work with so many institutions and artists, that this really bites back as you start to plan the opening shows, and critical curatorial needs are not in the project. It can be a source of great frustration.

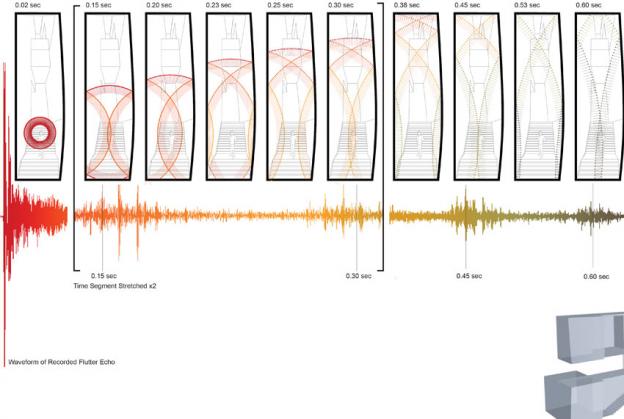

I’m particularly fond of one moment of delight in this project. There is a monumental stair that is a feature of the design. It connects all the floors and provides a vertical vista through the building. It provided an opportunity to design an acoustic moment for the building, where the sound is actively encouraged to bounce from wall to wall and up and down the building in a dynamic way and is viscerally responsive to visitors. There was an option to mitigate this out, but in discussion with Craig Dykers [Snøhetta] who was also a strong proponent of leaving it in, it was retained. Some were quite surprised at how responsive it is to just a light foot tap on a step, but everyone agrees it adds another element to the major architectural feature.

Back in NYC, the new Second Avenue Subway will eventually run the entire length of Manhattan. Arup’s acousticians were tasked with finding solutions to noise reduction due to the proximity of sensitive buildings, and to meet speech intelligibility requirements. Can you give examples of some of the steps you took?

An ambitious undertaking, long in the making, there were a few key acoustics issues the project presented. First was the impact of the construction and operation of the subway on both residential and sensitive hospital buildings along the route (many hospitals in New York are located along the length of Second Avenue). Since the geology varies along the proposed route, an extensive survey was carried out of existing noise and vibration conditions. This was used to conduct, analyse, and predict future impacts.

The most effective way to control noise and vibration is at the source, which usually on subway projects means the track must be isolated from the surrounding structures. There are various ways of achieving this, but they all have a fundamental impact on how the track form and tunnel are designed, so it is a crucial early design exercise that has knock-on requirements to all of the key disciplines at the early project stage. On the first completed section of the line, the track isolation meets the requirements of all the buildings around it, but also improves comfort to passengers on platforms and on trains in the system.

Achieving clear, intelligible messages on public address systems in the transport buildings plays two important functions. It helps provide a better overall passenger experience allowing messages to be clearly understood, whether that’s next train arrival or reasons for delays, but also crucially emergency instructions if and when needed. As with many new underground systems, the MTA recognized this need and welcomed our international experience in how this had been achieved elsewhere.

In your rare moments of downtime, do you still play an instrument, and what are your current musical influences?

I’m always noodling around with something, usually bass guitar, playing imaginary soundtracks to the TV with the volume turned down. I don’t play live as often as I would like. My tastes are quite diverse, but I‘ve also found my relationship to certain records changes over time too. I’m listening to a lot of Miles Davis’s later work at the moment, some of which I didn’t get back then, but really resonates now. The band Bauhaus is always a perennial favourite, and currently touring again and they are thrilling live. I’ve also been listening to a lot of Lou Reed recently, having been involved in the design of an exhibition highlighting work from his archive, which also includes a listening room, and opened at the New York Public Library for Performing Arts in June (through March 2023) called “Caught Between The Twisted Stars”.

One final question, please. Arup has been a valued member of TenderStream since way back in 2009. Do you think the practice has found it to be a useful service?

Absolutely! I have known Michael Hammond (founder of WAN and TenderStream) for much longer than that, advising and collaborating with him on his book (Performing Architecture: Opera Houses, Theatres and Concert Halls for the Twenty-first Century). That was happening while I was based in the UK and also working a lot abroad, and overlapped with my move to New York. He was talking then about his ideas about connecting the global architecture community together. He asked me to trial TenderStream in the early stages and provide him with feedback which I happily did.

It continues to be incredibly useful – the presentation of opportunities by location, and sector allows any user to tailor its use to their strategy, and allows you to streamline activity really well for global coordination and collaboration. It shines a light on unique projects and hidden gems. One thing I have particularly liked is the ability for me to find projects I think are well suited to up and coming and developing practices as a means to expand those relationships and help them find good opportunities they would otherwise have missed.

Arup SoundLab | Engineering the World: Ove Arup and the Philosophy of Total Design

Interview by Gail Taylor, Features Editor

IMAGE CREDITS

1 - Westminster Station, London - © Arup

Platform view with screen doors (right), sound absorbing panels behind perforated metal (top left) and loudspeakers located in contiguous linear infrastructure with lighting

2- Snape Maltings, Brooklyn, NY © Matt Jolly/Snape Maltings

View of the hall from the rear stage (note cool air supply through black slots in side walls for peak season)

3 - Snape Maltings, Brooklyn, NY © Matt Jolly/Snape Maltings

View from rear seats – note adjustable curtain deployed on stage for rehearsal

4 - Snape Maltings, Brooklyn, NY © Angela Moore/Arup

Exterior view – note upgraded roof-mounted hoods to exhaust air for natural ventilation

5 - Brooklyn Steel, Brooklyn, NY - © Arup

View of the venue with sound absorbing treatment behind wire mesh visible on side walls

6 - Brooklyn Steel, Brooklyn, NY © Mike Van Tassell

View to front of venue showing of green roof used to increase sound insulation performance.

7 - Brooklyn Steel, Brooklyn, NY © Mike Van Tassell

Note the dense housing development surrounding the venue – this was a key driver for the roof sound insulation strategy.

8 - National Sawdust, Brooklyn, NY - © Floto + Warner

View of the hall interior from the upper balcony

9 - National Sawdust, Brooklyn, NY - © Floto + Warner

View of the lobby to the hall – seen to the left is a vertical sliding door that allows the hall to be coupled to the lobby for events that also acts as a dramatic “unveiling” of the room for arriving audience

10 - San Francisco MOMA, California - © Arup

Top-lit gallery with sculpted ceiling optimised for light and sound dispersion. The upper concave portion focuses sound into the return air plenum above the ceiling to reduce overall reverberance and sound energy in the gallery space; the lower convex portion scatters sound to provide a more diffuse sound field in the gallery space.

11 - San Francisco MOMA, California - © Arup

The City Stair

12 - San Francisco MOMA, California - © Arup

Acoustic signature of city gallery stair.

13 - San Francisco MOMA, California - © Arup

White Box Gallery

14 - Second Avenue Station, New York © Charles Aydlett AECOM-Arup

On the platform at 96th Street Station, the noise-absorbing panels made from ceramic, metal, and mineral fibre are clearly visible, inset into the wall.

15 - Second Avenue Station, New York © ARUP

Rails are fastened to the ground via concrete blocks that are separated from the track from concrete by rubber boots to mitigate the rumbling as trains enter and leave stations.

16 - 17 Caught Between The Twisted Stars exhibition, New York © Arup

18 - Caught Between The Twisted Stars exhibition, New York - © Max Touhey and NYPLPA