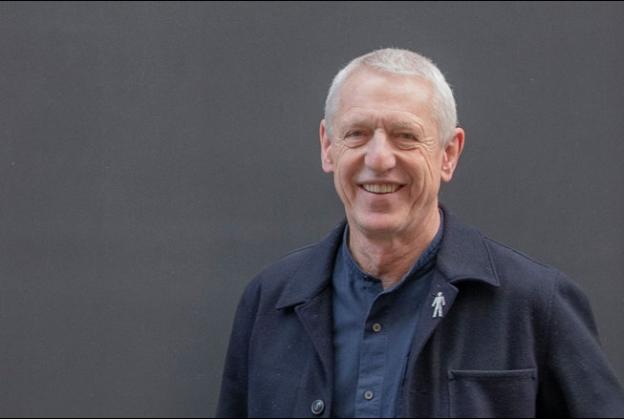

Alison Brooks - Founder and Creative Director, Alison Brooks Architects

Annalisa Hammond was fortunate enough to meet up with Canadian-born Alison Brooks, founder of leading international practice, Alison Brooks Architects. During their conversation, they discussed Alison’s views on a wide range of topics - from women in architecture to the challenges facing smaller firms in winning the big projects, to the thinking behind her iconic residential and educational projects.

Alison sees architecture as both an enabling social art and a creative cultural dialogue offering new forms of civic identity. This has led to over seventy awards for design quality. Alison Brooks Architects remains the only UK practice to have won the RIBA Stirling Prize, the Manser Medal, and the Stephen Lawrence Prize.

Read on for some fascinating, and perhaps controversial, insights from Alison…

We hear ABA is hiring. Sounds like you must have lots of exciting new projects in the offing.

Yes, we're busy hiring - we've hired around five people in the last month.

How many do you have in the firm now?

We're about 30 now.

So that's a lot to be hiring at one time?

It's a big chunk I suppose! Architectural practice today is all about managing unpredictability. We have exciting new projects but it’s also about progressing to new stages of current projects. We have new or early-stage commissions in Cambridge and Brussels; Toronto Quayside; ABA’s tallest building (62 storeys) is about to start; and we've moved into the next stage of the International Quarter London (IQL) Park Place on the two towers that we are doing in the Olympic Park for Lendlease. We always have some sort of research, projects, and competitions going on.

You are very well known for groundbreaking residential projects; do you still have to compete for projects in this sector?

We tend to be approached to do residential projects; I only do one house at a time. So, I'm very selective about the private houses because they're kind of an R & D process. They're very intensive projects that require a lot of effort and energy within a relatively small scope, but very valuable. As we are approached to do housing projects, the cultural and public projects are the ones that we compete for.

We were one of six finalists chosen to prepare designs from 190 international submissions for the London School of Economics’ Firoz Lalji Global Hub and Institute for Africa.

And I assume opportunities like this still get your heart racing? Not just commercially, but because you would love to work on this project?

Absolutely. University buildings have such an important role to play for the sort of academic communities that they're serving, but also as pieces of the city, and nearly all of them are open to the public for events, lectures, and talks. And so, I think they play a crucial role in broadening access to education and knowledge and debate. This project will have a space called the Agora, which is a significant debating chamber. I think the idea is modelled on the sort of UN General Assembly. So, these kinds of spaces are really important pieces of civic infrastructure. You couldn't really ask for a better project brief. The London School of Economics has established a reputation for commissioning very high-quality architecture.

It's important to work for a client or a client group that understands the importance of this, and it can affect the way people think and feel. And since they are end-users who are interested in the longevity of the building's durability, they invest in design quality.

Exeter College Cohen Quad recently won RIBA South Building of the Year Award 2022 and is described as a ‘reinvention of the collegiate quadrangle’. Could you tell us a bit about it?

So, the column quadrangle is the sort of typology that is based on the ancient model of a teaching and student community that lives together and learns together in one building, or one compound. It's based on the monastery. This is how most of the ancient colleges began, and so it's a very interesting point of reference because it suggests the idea of a kind of self-sustaining community. Originally, they grew their own food and undertook all the rituals of everyday life, eating together, working, making things, and studying. Scholarly work that was maintained by the monasteries during the Middle Ages, for example. So that kind of incredible tradition of a college or a collegiate community is what underpins this project, because all Oxford and Cambridge colleges are based on that model.

I started the project thinking about that and thinking about how the spaces could link together in a way that evoked the monastic tradition with cloisters that frame courtyards that frame outdoor spaces, and buildings that allow you to see outside and see through the building. That's a very Oxford and Cambridge tradition. The buildings have such a narrow footprint, they're more or less one room deep, so you can see through buildings into landscape spaces. I call this double transparency; you look through one set of windows and another set of windows and then into a courtyard or landscape. I was working with that traditional narrow footprint, but rather than a four-sided courtyard, I transformed it into an S-shaped building that weaves between two courtyards and creates a journey that allows you to experience one kind of landscape space.

And was it hard to persuade the client that this was the best approach? Was your concept something they understood straight away?

Yes, they understood it straight away. It was in the competition submission, which was a fully developed, fully designed scheme, so the scheme that's built is the competition scheme and didn’t really deviate from that. But the most significant kind of reinvention was that I introduced a Learning Commons, at the centre of the building, enabled by the S shape; where the two arms create a new space.

It’s not a room, and it's not a corridor, it's an open four-sided space, with four half levels, that aims to be an informal, multi-level social learning space with lounge seating and study tables, partially enclosed rooms, and a café at the lowest level. So, it was all about making a building where the students and academics could feel at home and use the building like a house, and find their place within it.

All the teaching and seminar rooms have at least one wall that's glass, so you can hear separately acoustically, but you can see the movements through the building and see the sky and the weather changing, and feel connected to the context.

One of the sad results of the pandemic is that education and attending institutes of learning is not just about education, but about the whole experience of leaving home - often for the first time, socialising, living in a community, making new friends - and many young adults have missed this opportunity.

Yes, and often students who are studying disappear into their rooms and don't come out. And that's an issue at places like Oxford and Cambridge which are very intense environments. And so that was very much at the forefront of my mind, to find a kind of spatial arrangement, orchestrating the spaces in the building, so they would attract the students to come out of their rooms, and be in places where they could be seen, but not feel like they were claiming territory or invading somebody else's space.

So, the mental health of the students was a consideration in your response to the brief?

Absolutely. For me, I think it's creating an architecture or a place that offers students a sense of freedom so that they can occupy different parts of the building. It's Oxford's first fully barrier-free college, and its first project that has a dedicated social learning space. There is a sunken area, which has study tables and sofas and then there's a room that's suspended from the ceiling that's acoustically separated. On the other side of that space, there are more study tables on the stairs that go down to the café. The whole area has a kind of low hum and is incredibly popular.

It must be hugely gratifying for you.

Yes, it's fantastic to have made a space that's unlike anything the college has had before, and what I've been told is that the space has enabled different communities and different members of the college to come together in a way that they never had before in 100 years.

So, when you create a hugely successful award-winning project like Exeter College, do you still have to compete for projects in the same realm? And do you think there's an element of people asking architectural firms to compete because they can?

That's a good question. It's kind of a difficult topic, but it's an important one to raise. Because I think competitions do bring out the best in architects; they create a very concentrated and intense way of working through the limited timeframe of the common, although I mean obviously you must make it through a couple of stages before you make it to the final design shortlist. But that concentrated effort and teamworking, it pushes you to produce very rigorous and well thought out schemes. And then when the scheme is chosen, there's a very clear vision there that the client and the group have all bought into, so there is a huge momentum to speed the project through. There's something great about having a very clear vision to inspire everybody. And it also helps if buildings have the vision behind them to start getting supportive funds on board. The other side is that it's very expensive to participate in a major competition.

And no firm is going to win every competition, so how do you cope with the motivation issues if your team has designed a stunning scheme, worked late nights and weekends then it hasn't been chosen?

I don't think there's ever a motivation problem, the thing is that you learned a lot during the process. It is research and development, it does broaden your skill set and your knowledge base, and you have a portfolio piece. And so, it still has value and - to a certain extent - you think, OK, that was a good learning experience.

But a small firm that doesn’t have thousands of pounds to invest in a competition that may well respond with a stunning design, given the opportunity, might still miss out. I saw somewhere that larger firms like yours should collaborate more.

I did that with the LSE competition. I collaborated with a small practice based in Lagos, Nigeria.

That must have been interesting working with someone from such a different country.

It was. The practice principals were educated in the UK and in America, but they were born and have family and citizenship in Nigeria and Uganda. So, they bring an understanding of both European and Western norms in terms of delivering buildings, but also bring a kind of African perspective and African voice and a more diverse set of values and histories that I felt were very important to draw on in our project.

And how did you find them? And why did you pick this company to collaborate with?

Well, very, fortunately, one of my associates studied at the Harvard Graduate School of Design with one of the principals who subsequently went back to Nigeria. So that was very lucky. I mean, if we hadn't known about that practice, we probably would have just done some research and tried to find someone and reach out to make that relationship. And a lot of the teams I'm working on I've brought in smaller practices and voices to enable that kind of diversity.

Moving next to older projects, no interview with you would be complete without asking about your two Stirling Prize-winning schemes, Sky Villas and the Brass Building, part of the Accordia masterplan in Cambridge. Described by the judges as ‘high-density housing at its very best’, what do you think earned them that accolade, and what for you are the most successful aspects of the designs?

The most important quality of Accordia is its generosity. From a commissioning standpoint, this is the result of Cambridge Planning Department’s chief, Peter Studdert’s stewardship and oversight. Peter wouldn’t accept standard developer ‘products’ on the site. After Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios put together our team, our client (Countryside) instructed us to ‘design the best houses you can think of, within the site boundaries’. FCBS designed a brilliantly clear masterplan – mostly four-storey terraced courtyard houses, with very generous communal spaces. FCBS, Macreanor Lavington, and ABA all built on the legacy of the Georgian terraced house – generous footprint, high ceilings, beautiful proportions, with generous roof terraces, great quality brick, and careful detailing.

Accordia was a turning point in UK housing design. It shifted the emphasis away from ‘modernist form-making’ toward making a calm and generous framework for everyday life. I was trying to reinvigorate the tradition of the semi-detached house with our Sky Villas. They are split-level, with a triple-height dining room and a huge family room under the curving roof.

The Brass building was always intended as a marker building to enliven the masterplan’s overall consistency at the turning point of the main axis. It was my attempt to find an ephemeral, crystalline language for a multi-storey housing block, a language that would amplify the arboreal qualities of the site.

Also praised, the 84-unit Newhall Be in Harlow, Essex was said by the Stirling Prize judges to ‘demonstrate the added value that good architects can bring to the thorny problem of housing people outside our major cities’. Limited land availability was apparently an issue, so how was this tackled? How does designing for density sit with giving due regard to privacy?

Newhall Be was another one of my attempts to reinvent a typology – this time the lowly suburb. I took some lessons from Accordia’s courtyard houses and made them even denser in the form of back-to-back courtyard terraces, and merged them with the crystalline geometries I’d been working within the Salt House and the Brass Building. Newhall Be houses all have workspaces/home offices, like shopfronts. The intention was to provide a great space to work from home and bring economic activity and community life to a suburban development. Their home office is the residents’ favourite space. They were also made from prefabricated timber with very generous ceiling heights.

ABA’s Cadence is a mixed-use urban block within the King’s Cross Central Masterplan in London. How has it responded to its historic setting in terms of design?

It’s all about the arches. And the brick. Both were inspired by George Gilbert Scott’s St. Pancras Station. It’s one of my all-time favourite buildings.

Ely Court is a 43-dwelling mixed-tenure regeneration scheme within London’s South Kilburn Estate Regeneration masterplan. What factors informed ABA’s approach here?

This was my first opportunity to tackle a failed 1970’s estate, and one that I had known since I first moved to London. My approach was very straightforward: restore the street, bring the principles and generosity of the nearby Maida Vale Mansion Blocks to South Kilburn, but in a more contemporary form and mix. French doors, high ceilings, recessed balconies, and porticos to animate the facades – facades are also the public realm. [It’s about] celebrating the threshold moments in each building. 20th-century architects sacrificed these basic tenets of good housing design for the sake of modernist dogma. I design places that remind me of the best housing in the world, like Place des Vosges, housing where I would be very happy to live.

One of the things I would like to discuss with you is this... You are known for your support for women in architecture; what do you think is preventing more women from being as involved in architecture?

This is also a tricky subject. And I believe it's tied into the economics of practice, which is also related to your earlier question about competitions; that the cost of competitions, the competitiveness in terms of fees, we don't just have to compete in terms of the design, we also have to compete in terms of the fee level. I think this is particularly bad for the profession because very large firms that have commercial clients and are very profitable can clearly invest more in competitions.

I think the business model of architecture is very difficult, especially for women when they are at the point in their lives where they are just starting a family, and then the salary after the tax just about pays for the childcare. And so what's the point of staying in the practice and sacrificing spending time with your children? I think that is one of the biggest issues.

What's the answer?

One of the real problems is that since Thatcher’s government removed the mandatory fee scale, fees for architectural services have been pushed down and down and the profession had to open up to others outside the profession, and non-registered architects were able to produce buildings. This is not the case in North America and Europe for example, where architects must stamp the drawings of every building, there's a kind of professional authority, which comes also with liability, but also a standard, that means that those countries can have fee scales that everybody adheres to.

Local authorities must prove to their superiors in their governance bodies that they've achieved value for money and the lowest price. There is an obsession with competitiveness and value for money, as borne out in their procurement questionnaires. It has led to a race to the bottom in terms of fees.

When you set up your practice, did you intend to specialise in residential projects?

Yes. My thesis project in my final year of architectural studies was a huge regeneration project in Buffalo, New York. And I had to essentially reinvent an abandoned housing project from the 1950s right in the centre of Buffalo, so one of these kinds of notorious American projects. And I think it was even before the term urban regeneration existed, but I felt that the kind of European model of very high-quality architectural thinking being applied to urban housing to raise the standard of living and quality of life for disadvantaged communities - or for all communities and cities – was about fusing social projects and architecture. I think every architect has a duty to respond to that challenge.

So, when I started my practice, although one of my first projects was a hotel interior, and one was a private house, I started doing housing competitions immediately because I thought I must break into this sector which is very difficult to do somehow, so I did competitions: the European housing competition, an Urban Splash competition, the Marsham Street competition. I understood that as an outsider, a Canadian, who didn't have a lot of connections to practices or institutions or family or anybody in the UK, that the only way the practice was going to obtain those clients was through demonstrating architectural skill through design; there was no other route available.

And if you hadn't been an architect, what other career do you think you might have followed?

Photography is something that I love and it's something that I do a lot. Although I just recently started my own Instagram feed 10 years after everybody else, I see photography as being essential to the process of design thinking. I think in three dimensions, and I think spatially, and I picture what I'm designing in a way as photographs, or as a camera, and try to make sure none of those photographs are bad, or boring. And so, in a way, I'm always recording what I see. I always record details and moments and light and shadows, and I lock these memories into my brain as I photographed them…and I was always interested in graphic design.

And you have designed one piece of furniture, a stool. Would you like to do more?

I would if I had the time. It would be fun. Having worked with Ron Arad, I'm very critical and very demanding about what a chair does, or what objects do. So, I would enjoy that, but you have to dedicate a certain amount of energy into pursuing those sorts of things, and I'm more interested in making pieces of city and creating those contexts in which people experience life and form communities, learn, perform. So, for me, it's more about making those kinds of spaces accessible to everybody.

And is there a type of project that you haven't done yet that you'd like to?

I'm actually designing a small art gallery right now (that I can't really talk about) but it's wonderful to be working with an art collection and designing spaces for art. And, it would be wonderful to design a library - an actual library with books, before they disappear.

Outside the demands of heading up a world-leading studio, what would we find you doing in downtime?

Probably the most protected downtime I have is skiing. I really love skiing. I've skied my whole life. And that's one of my other alternative occupations - if I hadn't been an architect, I think I would have loved to have been a downhill racer, a competitive skier. So, obviously, that has a limited timeframe - the careers of downhill skiers are relatively short. But when I'm skiing, that's a very immersive experience. You must completely focus; you have to be disconnected from technology. And it's wonderful to be in the mountains. I love the kind of total commitment and adrenaline that comes from skiing.

And then every summer I go back to Canada, and I live on an island for a few weeks with my family. I'm not disconnected there, unfortunately, with 4G available. I still check my emails, and I'm still in touch with the office and I've done competitions, in fact, quite a few competitions. Because many clients launch their competition at the beginning of the summer, and then they go away on holiday. And then when they come back ‘voila!’ - a scheme. But I don't mind it. I’ve done it now for 25 years. And it's still a joy to design and to think and to be challenged and to address new problems and situations.

Do you think the wider society really appreciates the importance of good architectural practice?

The effort and the passion and the commitment of architects as a profession is pretty remarkable and it reminds me of a statement that my Winward House client made, which is that 'there's no better value than having an architect design your house', and it's very true, given the number of decisions that architects make about everything to do with the project; sighting, construction methods, materials, organisation, long-term performance. It really is an incredible example of the combination of bringing technical expertise but with artfulness to somebody's everyday life, and I think a lot of institutional clients would say the same. Architects provide very good value for money because their fees are a tiny percentage of the overall project cost.

IMAGE CREDITS

Alison Brooks - ©Ben Blossom

1 - 3 LSE Firoz Lalji Global Hub, London - ©ABA

4 Exeter College Cohen Quad model - ©ABA

5 Exeter College Cohen Quad, Oxford (building process) - ©Fran Monks

6 Aerial View_Cohen Quad, Oxford - ©Studio8.

7 Exeter College, Oxford - ©Hufton+Crow

8 Courtyard, Exeter College Cohen Quad - ©Paul Riddle.jpg

9 Learning Commons, Exeter College Cohen Quad, Oxford - ©Hufton+Crow

10 Porter's Lodge, Exeter College Cohen Quad, Oxford - ©Hufton+Crow

11 Accordia Sky Villas, Cambridge - ©Tim Soar

12 Accordia Sky Villas, Cambridge - ©Cristobal Palma

13 Accordia Brass Building, Cambridge - ©Paul Riddle

14 Newhall Be, Harlow, Essex - ©Paul Riddle

15 Cadence King's Cross, London - ©ABA

16 Ely Court, London - ©ABA