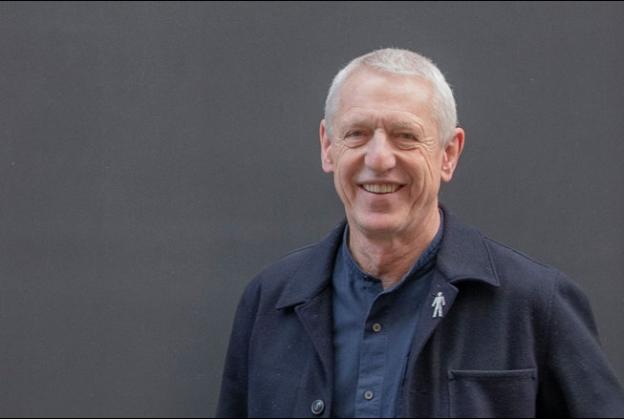

Kai-Uwe Bergmann, FAIA, Partner – BIG (Bjarke Ingles Group)

If one word was to sum up the spirit of BIG partner and business development leader, Kai-Uwe Bergmann, that word would be ‘pioneer’. Since university, he has always taken the uncharted path, voyaging, discovering and learning, never blindly accepting the norm just because it is considered to be the norm. After joining BIG in 2005, he has worked on countless stellar projects, including the vast energy-plant-cum-roof-top recreational eco-destination, CopenHill, in Copenhagen, and the ethereal sculpture park bridge and art gallery, The Twist, in Norway.

In this fascinating interview with Kai-Uwe, he shares with us the thinking behind some of these projects. He also airs his opinions on why architects need to be more politically proactive, and explains his views on taking a ‘Viking’ approach to architecture and to life in general. He also gives some sage advice to students of architecture based on his own (very varied and unusual) experiences. Read on to find out just what some of his intriguing ‘apprenticeship’ adventures entailed….

When you met at the Venice Biennale in 2004, Bjarke Ingels described your portfolio as ‘a funky combination of glass blowing and a clay temple in Central Africa’, and subsequently offered you a job in BIG’s Copenhagen studio. But how did you come to have this very diverse and unusual offering in the first place?

When I studied architecture in the United States, I first did my undergraduate degree at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, where I got my Bachelors. Then, I went on straight to the University of California, Los Angeles, where I got a Masters of Architecture. That was six years of education, and I really felt that I had mastered the art of building out of cardboard and chipboard. While you’re learning the theory of architecture, the history of architecture, and also designing while at school, there were a lot of things I felt I was missing.

So, for two years after school, I set out on an apprenticeship journey, which took me to West Africa, through Siberia, the Baltics, Europe, and Hadrian’s Villa in Italy. I worked with adobe architecture in West Africa, I worked with the stonemasonry in Lithuania, I served as a surveyor at Hadrian’s Villa in Italy, and finally undertook glassblowing in Sweden. This was a grounding in the materiality of architecture, which I then integrated into my professional career.

Moving on to projects, let’s start with the BIG U, which addresses the issue of coastal defences around Manhattan’s East Side, while also providing landscaped public space. More than 1,000 participants from the community provided input at public workshops. What were the primary issues people raised?

The BIG U is what we call ‘social infrastructure.’ While it is infrastructure that is there to protect against sea level rise - a flood management system - it’s much more than that. It is also giving back to the community in terms of providing green space, active open space, so that when it’s not protecting you against storm surges or rising waters, it’s still a functional space. The questions that we asked of the local community were, what are you missing? What would you like to see? Because, as the city is investing in protecting the community, they can use the same dollars to also provide amenities that the community currently lacks.

The first two and a half miles of protection are in the Lower East Side of New York City, which is the area that had the lowest open, green space per capita in the entire city. So, we wanted to make sure that we were providing as much open, green, recreational space as we could while providing this protection.

Staying in NYC for the moment, can you briefly describe the thinking behind BIG’s winning entry into the Van Alen Institute’s ‘Reimagining Brooklyn Bridge’ competition?

Thank you for calling it the ‘winning entry’; unfortunately it was not the winning entry, but it was one of the finalists. In the end, I do think we won a little bit in that our proposal created a kind of ‘people’s bridge’ that is inspiring a rethinking of what the bridge can be. The bridge had previously, when it was first built, integrated public transportation – through a light rail - to move people from lower Manhattan into the new borough of Brooklyn. The bridge was moving around 425,000 people a day. In the 1950s, the rails were actually taken off the bridge and everything was prioritised for the automobile. Since then, only about 160,000 people move across the bridge daily. So, we’re actually moving fewer people across than the bridge than it was originally designed for.

As such, we wanted to recalibrate the bridge to prioritise bicycles, e-bikes, e-scooters and autonomous vehicles. We wanted to create a bridge that really connected the people of Lower Manhattan and FiDi [Financial District] with the borough of Brooklyn and further. In doing so, we showed a vision for how to integrate bike lanes into the car lanes. The current Mayor, inspired by our proposal, has just started the construction of those first bike lanes on the automotive lanes. So, that is in itself a ‘win’ for our vision.

Now to Denmark. Food lovers the world over know NOMA, the Michelin-starred Nordic cuisine restaurant in Christiania. BIG designed its latest incarnation (it has had a few); what do you think (apart from the food!) makes it so special in terms of what you’ve created there?

NOMA is really a manifesto that was created in the early 2000’s to examine how the Nordic region looked at food - a look at both its origin, its fermenting, and how food was foraged and pickled during the different seasons in the past. NOMA is a syllabic abbreviation of the two Danish words "Nordisk" (Nordic) and "mad" (food). René Redzepi, the main chef, is one of the original founders of this movement.

When you start to look at the actual design of our latest restaurant, you’ll notice that it’s almost like a village. There are 11 different buildings, one of which is actually a former bastion from hundreds of years ago, which include the main back-of-house areas for the cooking staff, the outside greenhouses, the pre-dinner arrival area, the BBQ pit, an intimate room for private events, the dining room area, and of course the hearth/kitchen. These spaces are all little buildings; they’re rooms within rooms that allow each of the functions - food preparation to food serving to food enjoyment - to have their own space. They have their own materiality and light conditions, so that it’s a place where all of the senses are active, and where you can start to really think about the food experience, from beginning to end.

Sustainable design is a hallmark of BIG’s work. A truly unique example is that of CopenHill in Copenhagen. The vast waste-to-energy complex boasts a ski-slope and specialised landscaping on its roof, artfully blending industry with a leisure destination. What do you think it has brought to the city?

This is a project that has been about 11 years in the making. We won the competition in 2009. I was always fascinated that in Denmark, you would have a competition for an energy plant that architects were involved in, because primarily this is the realm of engineers. But this was a waste energy plant positioned right in the heart of Copenhagen, right next to Christiania, and a 15-minute walk to our NOMA restaurant, mentioned previously. It needed to be considered at the scale of urbanism. It couldn’t be just a power plant.

So, how do you integrate a plant like this into the heart of the city? We came up with the idea of really creating a recreational landscape. Not only skiing, but a walking loop, running paths, and a climbing wall, to really create an entire natural eco-system where birds and bees and flowers were cohabiting with people on top of a power plant - a building that would be typically cordoned off in any city, with no one being able to get close. CopenHill is a prototype of a new type of energy plant that we hope will take seed in other parts of the world.

BIG’s first project in Norway is The Twist, a torqued bridge over a river within the Kistefos Sculpture Park that acts as a gallery and an immersive space for visitors. What elements please you most, and why?

The Twist is doing three things. The first is an issue of the site, a former mill, with the river running through the middle. The mill no longer functions as a mill, so it has been rehabilitated into a museum. Then, there’s a very world-class sculpture garden on both sides of the river. Previously, when people would visit, they would walk on one side of the river, have to track back to the mill, and then walk the other side of the river. It was a very circuitous route that would oftentimes force you to double back, seeing the same things that you’d seen before.

By actually building a bridge over the river, we could create a loop so that everyone could walk around and see the sculpture garden, and really enjoy it without missing anything. So, the Twist acts as a bridge, a very functional object-like bridge.

The Twist is also an art gallery. While you’re on this covered bridge, there are ever-changing art exhibitions and installations that can be viewed within. Every time you come back to the museum, you see new works. That is absolutely beautiful. Finally, the twisting shape creates a piece of sculpture in itself, just like all of the other sculptures in the landscape. So, it’s not just a building, and it’s not just a bridge. The Twist elevates the entire program and its look and feel to that of the artworks that are in the landscape.

Another highly ambitious project is that of the South Penang Islands in Malaysia. It involves the sustainable development of three islands for future generations of the residents of Penang. Can you share with us the vision, and what has driven it?

Penang is a city that has a lot of economic dynamism. It’s also a place where a lot of different cultures in Southeast Asia come together. It is surrounded by a beautiful coastal area. The city itself has very little room for growth because of the geography. So, one has to start thinking about how and where the city could actually grow.

If we look around the world, almost every coastal city, at one point or another, starts to sculpt and create man-made land, reclaimed land, in their coastal areas. This is Penang looking at a way to expand intelligently to the South, where a lot of the development trends are heading, and to create an infrastructure hub that also considers the ecological balance that needs to be made between the natural eco-systems and the man-made ones. So, it’s a very eco-system-centric urbanism on how to prepare for the future so that it’s also environmentally sensitive.

In one of your many student lectures, you referred to leadership starting with the individual. How does that translate into the things you have done to be a leader in your own life?

I believe there’s a certain optimism in the way one can approach life. When I graduated, I decided to take a path that was less travelled. So, not your typical internship and office-based job, but rather, the apprenticeships I described before. I think that I looked at these experiences as a collection of skill sets, and being able to speak to carpenters and glass blowers and stonemasons. In a way, this collecting of experiences gave me both insight and confidence in the way that I entered the profession of architecture.

In the same way that I looked for my own path after school, I looked at my own path within BIG when I noticed that as an architect, and being a project leader, that there was no-one really looking at where future projects were coming from. Everything was a little bit based on word of mouth, and who knew Bjarke. I realised that I needed to delve into business development - something I'd never been trained in.

Just as I looked at the apprenticeships, by ‘doing’, I was learning; I could make things happen that I otherwise couldn’t if I was just sitting there waiting for other people to take over. So, that mentality of going and trying things out and approaching it from an optimistic point of view has been the way that I’ve viewed being a leader in different times of my life. I would say that you can lead at any point in your life if you reframe what it is that you are doing. You shouldn’t just accept the society or professions’ definitions of leadership or what structures exist around you. You can very much create your own path. I think that’s also what’s so exciting about architecture - there are so many paths to take. My advice to anyone is to chart your own path.

What’s the most valuable piece of advice would you give to a student of architecture?

There are two ways of learning; you can sit in a dark room at a university and learn by soaking in all of the knowledge around you through your professors and classmates. The other learning happens when you go out and see places for yourself. I think that both are equally important.

What I would suggest to students, since you’ve done the bookish part and you’ve been in a university setting, is to compliment this experience with the experience of seeing and doing things for yourself. Don’t only rely on second-hand accounts. The most important thing you can invest in is yourself, through travel. Through traveling, you will build a life experience that you’ll always draw upon, no matter where you are in life or how old you get. You should travel when you are young, as this will benefit everything that comes after.

It’s well-documented that you feel architects should have much more of a say in the political landscape in order to foster more sustainable, more humane developments and policies. But how do you think they can actually go about achieving that?

If you are living in a democracy, then you have a representative government. What I’ve always found so fascinating is that when you look at Washington D.C., at Congress, it represents mostly bankers, lawyers, and doctors. It almost seems that you’re needing to come from one of those backgrounds to enter into the House of Representatives, or the Senate.

I ask myself, where are the architects in this political landscape? Where are the skill sets that we learn as architects - thinking holistically, long-term planning, re-thinking systems and transportation? I feel that becoming engaged politically is important; in the end, everything comes down to policy, and the way that the cities are zoned, the way that things are planned, and the buildings and the spaces in-between them are a direct mirror of the policies that are made by policymakers. If we’re not a direct part of policymaking, we can be reactionary. I think we can be a lot more proactive if we engage at that earlier stage, which is policy and politics.

On a more personal level, you were born in Germany, grew up in Georgia, USA, went to university in Virginia, spent time in Denmark, then finally settled (or maybe not) in NYC’s DUMBO [District Under Manhattan Bridge Overpass] in Brooklyn. What were some of the most vivid impressions and emotions you experienced along the way?

I do believe that I am made up of different facets in different environments. I view my life as chapters of a book, where the geographical setting is very much the beginning and the end of the many chapters of my life. I feel very European when I live in America, and I have felt very American when I have lived in Europe. There are little parts of me that come out as a result of my surroundings.

The one thread through it all is that I probably feel most Viking in the way that I approach both life and business development. It’s about going to uncharted territories and places we haven’t been, or typologies we haven’t built, and trying to create opportunities in each of these places, much like the Vikings did. So, I’m a little bit American and a little bit European, with a whole lotta Viking in-between!

BIG’s New York practice is located where you live, in DUMBO. BIG has moved around a few locations in the city in recent years, so how is the new office working out for the team?

We have been in a few different neighbourhoods in New York City; each one, from Tribeca, to Chelsea, to Manhattan’s FiDi, offering us tremendous support in regards to providing us with a creative environment.

We’ve always outgrown the space; thus forcing us to move. The last move was to DUMBO in Brooklyn, a borough where most of our staff live. It’s nice for them to be working either in their own neighbourhood, or very close to it. DUMBO is one of the greatest neighbourhoods in Manhattan at the foot of the Brooklyn Bridge. You have the Brooklyn Bridge Park adjacent to these 100-year-old warehouse buildings. I very much think that BIG NYC will stay and remain in DUMBO for the foreseeable future. I think we’ve future-proofed ourselves after the fourth move, so that we don’t have to keep moving around.

What led you into architecture? Was there ever any other career you might have considered?

One of the biggest influences for me was traveling at a very young age with my parents. I would always enter these cathedrals and castles and be amazed at their spatial grandeur, the materiality, the acoustics, the permanence. All these things really impacted me. When I thought about what I wanted to do in life, I felt that architecture wrapped up all of the different interests - from history, to anthropology, to culture, to the arts, to drawing - all of these things were manifested in architecture so it was a natural choice of path for me.

And we have to ask, what possessed you to cycle up to 200km a day, mostly uphill, over The Andes back in 2014?

Every two to three years, the partners at BIG have gone on a trip abroad. These trips have always involved mountain ranges or traversing natural landscapes. The first trip we took together was scaling Mount Kilimanjaro, then the second was over the Andes by bike, and the third was snowshoeing a traverse in the Alps.

These trips offer us a chance to de-couple from our work life and spend important times together; we encounter a challenge, and work together to overcome the challenge, which might mean reaching a summit, or failing but supporting each other through it collectively. These activities have been really important.

I’ve not been on every trip. I was having my first child, Amelie, and missed skiing across the inland ice of Greenland over a week, which involved going over a ridge that is on the spine of Greenland. That nearly took some partners out. Experiencing a near-death experience together makes you that much stronger as a group. Those trips have been really formative for the trust and the bond that exists between us.

And finally, as one of our valued members, may we ask you if the TenderStream service has been useful to BIG over the years?

I think that when you’re in the line of work of finding new business opportunities, TenderStream plays a really, really important role, because you simply can’t have your eyes and ears in every place. The world is too complex, and too varied for that. TenderStream is an incredible tool that will always shine a light upon a project here or there that would otherwise go unnoticed. It reinforces the leads you already know about, and finds the hidden gems that you would otherwise miss because it’s usually all needles in a haystack.

Interview by Gail Taylor, Features Editor

IMAGE CREDITS

1 - 2 Brooklyn Bridge - Images BIG Bjarke Ingels Group

3 - 4 NOMA - Images Rasmus Hjortshoj & BIG – Bjarke Ingels Group

5 - 6 Copenhill - Images Rasmus Hjortshoj & BIG – Bjarke Ingels Group

7 - 9 The Twist - Images Laurian Ghinitoiu & BIG – Bjarke Ingels Group

10 - 11 South Penang Island - Images Lucian R & BIG – Bjarke Ingels Group