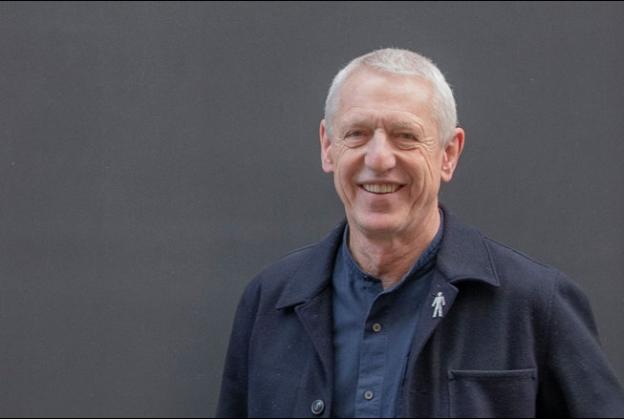

Nicholas Reynolds, Senior Principal - Populous

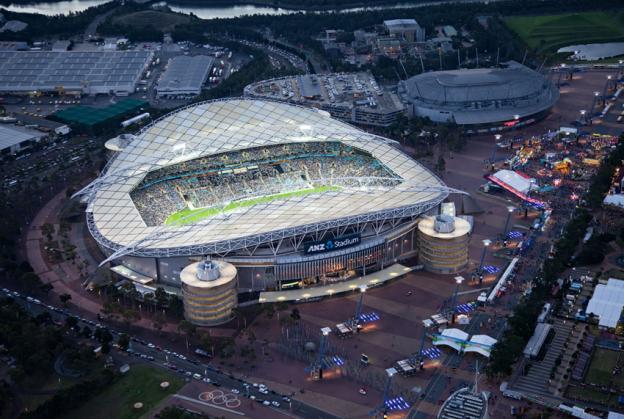

When Nicholas Reynolds was offered the opportunity to work on the Sydney Olympics Stadium back in 2000, he leapt at it, leaving behind the world of residential architecture. Since then, he has never looked back.

As a designer (and now Senior Principal) at international venue-specialists, Populous, he went on to work on world-famous venues including London’s O2 arena, the Centre Court at Wimbledon and the London 2012 Olympic Park. In this interview, he shares with us the stories behind the huge success of these iconic projects.

Nicholas also gives us some fascinating insights into the profound ways in which stadiums and arenas are being shaped and transformed by technology, and how branding has evolved from just being ‘a badge on the side of a building’ into an integral part of the thrill of the venue experience. Read on to hear what he has to say…

To begin with, what is the significance of today’s digital ‘document and share’ culture in terms of how you would design a modern stadium, and how does that contrast with, say, 30 years ago?

Fans visiting stadiums are now so much more aware of the full breadth of experiences available in different markets and around the world. In the past, perspective was more limited – even for the die-hard supporters who travelled home and away, the grounds you visited, coupled with those you saw on TV, gave you a limited understanding of what was on offer.

What’s happened with the document and share culture is that we’re now getting unfettered access to buildings and places – and particularly stadiums and arenas that are hosting high-profile events. Nothing is stopping us now from finding out exactly what any given stadium looks like and the range of experiences it offers – from the experience of sitting in the bowl to the hospitality, pre-game atmosphere and build-up – even back of house facilities like the players’ changing rooms can be found online through official channels and social media accounts.

So as a fan, as a supporter, and as an architect, you’re so aware of what everybody’s building and what experiences are on offer. This certainly impacts your mindset as a designer – you’re driven to deliver something that’s unique, identifiable, and that the fans are proud of and want to take ownership of.

Even 10 years can see huge changes in the way we live. How might this affect the next incarnation of major stadiums?

Two things are driving this – one is digital and the other area is sustainability, health and wellness. Historically, it has always been about fans wanting to be in stadiums in order to be present, in the bowl, to experience the game or sporting event. We’re seeing a generational shift of fans and spectators really questioning the broader cost of travelling long distances to watch events in person, holding event organisers accountable for the carbon footprint generated. However, they still want to feel part of the event or moment. So, you will begin to see far better use of technology to convey the experience of an event to remote audiences.

The flip side is that the in-person event – whether that’s a football match or a concert – will become even more prized, and because of that, the design of the venues themselves will continue to place an even greater emphasis on providing exciting and immersive experiences. Furthermore, venues will package that experience with bespoke individual digital memories for their customers, allowing those who are physically present to immerse themselves further in the experience in real time, comforted by the knowledge their moment is ‘captured’.

In terms of sustainability, you’re going to see an increasing number of artists question whether they’re going to do 50 dates globally, based on the carbon footprint of their touring entourage and travelling fans generate. We’ll see tours condensed to a single night, with one event tailored to being experienced simultaneously by an audience of 250,000 people through the multiple lenses of a live show, remote festival audiences and an at home VR experience. The combination of digital infrastructure and considered design that provides for an enhanced remote experience will be key going forward.

Obviously, stadiums do not exist in a vacuum. In projects such as Fulham FC’s redeveloped Riverside Stand, how do you go about integrating them with the wider community that exists around them on a daily basis?

Stadiums – and particularly football grounds – have always been at the heart of communities in the sense that they were the focal point for the events hosted within them. But there is an acknowledgement and understanding now within the industry that these buildings are part of the urban fabric and should be available as an asset not just for the club, in the case of a football stadium, but for the community as a whole throughout the week and year-round.

And so, as an architect, from the very outset of a project, you are prioritising the design of a building that comes alive 365 days a year.

Our design for the new Riverside Stand for Fulham FC is a perfect example of this. From the very outset of the project, our focus was on creating an amazing bowl experience on the one side, but also to have facilities behind the seating bowl, facing out towards the river, that would offer something new and incredibly exciting for fans and the local community on both match and non-match days.

The shift in mindset is a subtle one but significant – the facilities are supporting and enhancing the sporting experience, but they’re not dependent on it. And this means that you approach the design from a very different angle, creating environments for a far more diverse audience, which in itself leads to more dynamic and flexible spaces.

You were involved in the transformation of the London 2012 Olympics Stadium. What has been created there now, post-Games, and what have been some of the biggest challenges?

The concept from the beginning of the project was to touch the ground as lightly as possible with a transformable and multi-use stadium, and the design has been incredibly successful in that regard. I’ve been lucky enough to see athletics, football, baseball, rugby, and music concerts at the stadium. The stadium was always intended to be a pavilion in a beautiful landscape, and the varied event programme at the venue over the years has been central in establishing the Olympic Park as a new destination in East London, and a catalyst for regeneration. Like all venues it will evolve as the event programme changes over time, but the intent was always to create a building which was sympathetic to this reality.

The challenge for the stadium and the wider Park has been in “bedding in” and supporting the growth of the sort of independent businesses – pubs, restaurants, workplaces - on approach and around it - that create an authentic wider event experience alongside the time spent within the stadium. That doesn’t happen overnight; it takes years, even decades.

And now to the great British weather at Wimbledon. Populous was tasked with designing the retractable roof over Centre Court in 2009. Part of the brief was to maintain the Champagne and strawberries ‘English garden’ vibe while also introducing hi-tech solutions so that spectators and global broadcasters (not to mention the players) could enjoy the tennis regardless of rain. How did you go about achieving this balance?

The identity and feel of the tournament is “tennis in an English country garden” and that runs through everything that’s done at Wimbledon, from the concession stands to the hospitality facilities and the in-bowl experience. Our intent in creating the retractable roof for Centre Court was to create an environment that would be conducive to play – but would also foster this spirit.

It was a very organic process. The design had to take into account the protection of the playing surface, acoustics, temperature control and humidity. In my mind, we were creating a garden room – an environment that maintained the integrity and character of the tournament to the point where spectators wouldn’t even notice the roof – they would remain totally focussed on the play.

Entering a major stadium feels almost like being on a cruise liner – everything must be considered and provided in one place – exterior, interiors, retail, facilities, and a ‘wow’ factor that transports people when it comes to atmosphere and creating vibrant memories. What do you think people expect from their stadium experience, and, as a practice how do you draw all the different threads together?

There’s not just one type of fan or person with a single expectation of the stadium experience – and, for me, that’s what makes it so fascinating. Our venues have so many different user groups, covering multiple demographics, and when we’re designing, the balance is always between making the experience specific to one or more of these user groups and making it accessible to all.

We have more information now than we’ve ever had about the people who use our buildings, which can be used to paint an incredibly detailed picture of how people are likely to interact with different spaces and experiences. But the real art is in using your designer’s intuition to create the sort of spaces that appeal to multiple demographics – creating spaces that can be dialled up or down depending on the user. That’s where the difference is between good stadium design and great stadium design.

In 2004 you founded Populous’ in-house brand activation and experiential design studio, which specialises in connecting brands to sporting and entertainment venues, and delivering commercial value. Did you have previous experience of branding, and can you give us an example or two of how brands and stadiums have successfully dovetailed?

Prior to 2004, we were finding that there were a number of somewhat successful examples of naming rights activations at stadiums, but it was never true brand activation – it was a badge on the side of a building. Then there was a shift towards a more complete experiential brand activation.

The first project to embrace this in Europe was probably the O2 Arena. From a design and brand strategy perspective, the partnership between the venue client and O2 was approached as just that – a partnership. It was seen as something more than just advertising – it was about what O2 as a brand could bring to the table in terms of an experience – how the brand could be used to enhance the venue and the experience for all visitors. In parallel, for O2, the association with the destination allowed their brand to be viewed through an entertainment lens and helped them connect with a new audience or customer.

After the O2, what you started to see was a move towards this type of synergy between brands and venues across the stadium world too. It showed everybody the potential of having the right partner in terms of boosting publicity and ticket sales, and also how having the right partner who shared your values would, by association, show people what you stood for as a team and stadium owner.

Even today, for me, the O2 is still the most successful example of brand activation at a venue to date.

You started your career in architecture designing individual houses and went from that to working on the 2000 Sydney Olympics Stadium. What prompted the move to such a large-scale non-residential project, and how did you manage to make that move?

The move came very much from an aspiration to shift away from residential architecture into designing something more experiential and ‘live’. I had moved to Australia, and the opportunity to work on the stadium for the 2000 Olympic Games came up and I fell in love with it instantly. What I loved about it more than anything was the lack of pretention, the consideration given to designing the building for a huge audience – not just a singular client – and the understanding that you weren’t just designing for an audience of spectators, but for a city and, in regards to the Olympic Games, a significant moment in time.

You have an extremely impressive portfolio of stadiums under your belt, are there any that are particular stand-outs to you, and why?

I always wanted to work on a variety of projects, so in a way the diversity of venues has been the most memorable factor – the differing challenges presented by the Oval cricket ground, Wimbledon’s Centre Court sliding roof, two Olympic stadiums in Sydney and London, then diverse arena projects from the O2 to the MSG Sphere and the Co-Op Live arena in Manchester. I’m more interested in taking on new challenges and new types of projects than staying within one particular typology.

If I had to pick an area I’m most passionate in, though, it would be the arena market because it’s so dynamic and so impacted by technology, with such a diverse range of content that takes place within the venues. In many respects, the feedback loop is more immediate in the arena typology than any other sports and entertainment market sector.

You mentioned in one of your TED Talks that you liked running. Are you a sports fan in general? And what would we find you doing in your (undoubtedly rare) spare time?

I’m both a massive sports and music fan. If I wasn’t an architect, I’d love to be a sportsperson – and I think a lot of people in the sector feel the same way, which is part of what gives you such a buzz from designing these venues. I’ve played a lot of cricket and golf, I run in my spare time. I’m a big West Ham fan and I love going to see music concerts – so it’s not just my career, it’s very much my passion outside of work too.

And lastly, as a valued member of TenderStream, can we ask if you and your colleagues at Populous find the service helpful?

As our marketplace becomes ever more mature and complicated, it’s incredibly valuable to have a single source that can provide us with details of opportunities we might be interested in.

Interview by Gail Taylor, Features Editor