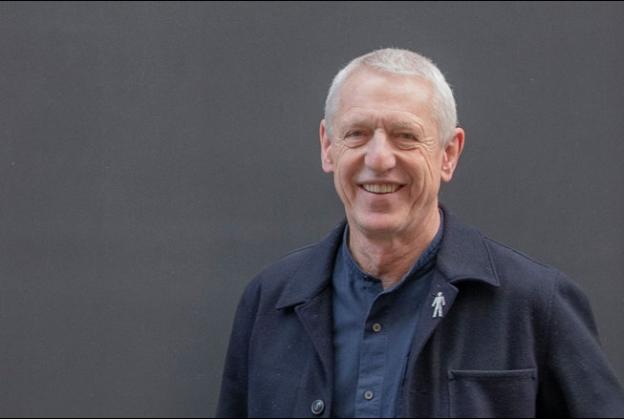

Elif Tinaztepe, Principal - Schmidt Hammer Lassen Architects

Schmidt Hammer Lassen Architects (SHL) operates from studios in Copenhagen, Aarhus and Shanghai, and boasts a prestigious track record as designers of international high-profile architecture. The practice is deeply committed to Nordic architectural traditions based on ‘democracy, welfare, aesthetics, light, sustainability and social responsibility’. Although working across many other sectors, the practice has an enviable reputation for its work on libraries, many of these designed by Principal, Elif Tinaztepe who joined in 2005.

Elif is the embodiment of the practice’s profoundly empathetic and humane approach to design. In her fascinating account, we discover how early training as a classical pianist and her interest in composition translates into the work she does today. Caring deeply about each project and ‘walking in the shoes of the users’, she has spearheaded many benchmark library and cultural projects around the globe, from Denmark’s largest public library, Dokk1, to the State Library Victoria in Australia. Read on to hear about these and some of her other outstanding projects….

First things first: how did your specialisation in designing libraries come about?

I would not categorise myself as specialised in libraries, rather experienced in the design of spaces for inspiration, study, learning, and engagement. It all builds on experience from working on spaces that foster a connection, from the City of Westminster College in London to the ARoS Art Museum in Aarhus – these projects have all shaped my experience and approach through the years, and include elements that are important to truly understand when designing a library.

I believe that architecture is about production of culture - culture of working, engaging, living. Likewise, libraries are such a rich typology that touch upon so many different forms of engagement and experiences, that I often find myself applying this knowledge to other typologies.

In very large-scale libraries, such as the ones you work on, how do you maintain a sense of human scale and intimacy?

Our point of departure at SHL is always the human condition, and the human scale which informs and guides everything we do. I think the critical thing on large projects is having the ability to flex between multiple scales at once so that there is a natural and indisputable correlation between the big picture and the detail. Between the urban and the human. We talk a lot about scale and place on these types of projects and the experiential qualities of architecture.

We have a clear methodology that allows us to walk in the shoes of our users and reflect on how they might experience the building. We think of it as a vast undulating landscape that offers diversity in scale, use and experience. A place to engage as well as seek refuge. How can we use scale, visual connections, materiality, lighting, and acoustics to provide that diversity, yet make it very approachable and inviting? It is also about creating that sense of walking into a building, and it immediately feels like it has always been there, yet you never knew how much you needed it. A sense of enjoyment.

Libraries are known for being ‘quiet spaces’, is that a big challenge?

In my experience no two libraries are the same. While some may need to have a larger portion of quiet, and even silent spaces, for very good reason, others, such as Dokk1 in Aarhus, explore different types of rooms for interaction and inspiration where there are gentler transitions from one type of acoustic experience to another.

Therefore, my initial task is to establish the visions and values that will drive the project forward in dialog with the client and the users. What is the purpose of the spaces? What kind of behaviours do we want to encourage? And then, regardless of our conclusions, we work carefully with the acoustics landscape pretty much like a building material, as it has such a key role in our experience of space and how it ends up being utilised – or not. I am interested in creating a differentiated acoustics landscape in libraries as our needs do change often even over the course of a day, depending on tasks, preferences, and mood.

Moving on to specific projects, your first library for Schmidt Hammer Lassen was Denmark’s largest public library, Dokk1. It now represents a new movement towards hybrid libraries. A three-part question; how do you feel about the finished project, what has been the public’s response to it, and do you think we are going to see more and more of these multi-purpose facilities?

I think as a team, and it must be said there are quite a few incredibly talented people at SHL who have their fingerprints on this project, we really feel proud. A project like this really develops us as a studio – we grow as thinkers and architects and makers – we grow as human beings, and that is incredibly satisfying.

The public took ownership of the building from day one. This is of course also due to the extensive public engagement process we undertook during design stages, which created a place and a story for the library in the public consciousness long before the building made its appearance in the urban fabric. The building is now an important cultural platform. All the qualities we knew about Aarhus – the young energetic developing city, tightly knit innovation networks, a sense of community – found a “home” to thrive in Dokk1 and be very present and visible every day. This has certainly changed the city’s self-perception and that alone creates a huge impact.

We are told Dokk1 has been an inspiration already by its value-driven architecture and what it can do for the city. I personally really hope to see more projects like it because we desperately need them as societies, especially now.

At State Library Victoria in Australia, we find a grand monumental building married with the contemporary interior spaces you’ve created there. How have you achieved harmony between the original building and its modern-day functions?

State Library Victoria is comprised of 23 different buildings that have been realised over a period of 150 years. A very eclectic collection of spaces that clearly belong to different periods and felt very disconnected. Our point of departure was to peel back, uncover the qualities of each space and engage in an architectural conversation with them.

It was a bit of forensic work in the beginning where we used a lot of time getting to understand the essence of the spaces. Then we embraced the unique traits of each space and tied them together with a new and contemporary design line, in order to create connections throughout the library and opportunities for a multitude of functions that we expect a contemporary library to offer. We allowed the buildings to guide us. We wanted to celebrate the uncovered heritage details in their raw beauty, complement them with a timeless design and create spaces that are authentic and honest.

Working with a project that has gone through so many different iterations, one quickly realises that our own efforts are just one chapter in a continuous story. It’s very humbling. That’s why we called our project ‘a framework for evolution’ – and we hope that the generosity we have tried to build into the spaces with our design approach will help new generations enjoy the State Library as much as we have while working on it.

On the other side of the world in the UK, The University of Bristol’s landmark new library will accommodate learning and research space with capacity for some 2,000 new study seats, 420,000 books, and 70,000 journals once completed. What do you think made Schmidt Hammer Lassen’s design the competition winner?

That’s a project we competed for and won twice actually, and we are really thrilled to be able to move forward with it. I think our contextual approach and understanding of the sensitive context - which lies at the intersection of two conservation areas - and our architectural response to that, combined with our bold vision for the academic library of the future appealed to the University. Those elements are always supported with our collaborative approach and methodology where we see our clients and users as genuine partners in the creative process.

What new pipeline library projects are coming up for the practice?

We have quite a few in different stages of development across scales. Our transformation of T L Robertson Library at Curtin University in Perth, Australia is under construction. Dordrecht Huis van Stad en Regio is a multi-purpose civic building that includes the new City Library. The University of Bristol in the UK has recently received planning approval and we are excited to work on that. We are working in partnership with Goethe-Institut, reimagining their libraries across the globe. This partnership has given us access to geographies we have not worked in before, and we feel fortunate to be able to bring our skills and experiences into play in different cultural contexts. We are also closely following the development of library and cultural projects in Denmark, Northern Europe, and North America.

You once said that architecture was ‘an optimistic profession like no other’. Can you expand a little on what you mean by that?

Architecture is about creating opportunities where others see obstacles. By its nature, it seeks possibilities, a new way to overcome challenges. We dream of better ways to live, learn, work, and socialise. We aspire to create spaces that promote social justice and equality. Beautiful places that lift our spirits. Better ways to care for our planet that connects us all. So it is, for me, a very optimistic profession.

Were you always destined to become an architect?

Interesting question. My path was not linear – as in Lego bricks to buildings - I have always been intensely curious about too many things. I was interested in culture, cities, society, performing, obviously design and I was trained as a classical pianist from an early age and enjoyed composition quite a bit. Music has always been about that underlying order for me, the big concept, which you build upon to create something poetic and emotional which you share. Or you create an order to achieve the poetic result you visualised. In hindsight, architecture is perhaps the place where all those interests meet and can be made operational – so that we can move ideas and people to better places.

You were born in Istanbul, then went on to work in Los Angeles and London before moving to Denmark; all completely contrasting locations. What are some of your most vivid mental images of each, and how has such varied trajectory around the globe influenced your work?

Istanbul of my early adulthood is about contrasts. The meandering dense urban network, layers of history, the city as social space, and the Bosphorus Strait – which we all worship as it is both an escape and a breathing room as well as a place to connect personally and geographically.

Los Angeles is a special place that gets under your skin – infinite views from the mountains to the horizon and a real sense of freedom. A sun-drenched sound stage for its culturally diverse population. Both cities are great labs for architectural research and experimentation, in entirely different ways.

Mental images of Denmark are dominated by city centres that prioritise the human scale, a sense of shared ownership of public space, beauty discovered in subtleties and details and an incredible sense of design – all of which reflect the values we cherish in Denmark. I feel really privileged to call all these places home. They have taught me the importance of sense of place and have helped me develop cultural competences that allow me to approach each project – and geography – with zero prejudice, deep empathy, and a genuine curiosity. Given architecture is very much about context and people, I bring this perspective with me everywhere and keep building on it.

Lastly, Schmidt Hammer Lassen has been a valued member of TenderStream for some years. Has the service proved beneficial to the practice, and how would you rate it?

TenderStream provides us with the daily overview needed to follow new opportunities across the markets in which we work, in a very user-friendly format – it is our go-to platform.

IMAGE CREDITS

1 - Christchurch Central Library – Photo by Adam Mørk

2 - Christchurch Central Library – Photo by Adam Mørk

3 - City of Westminster College – Photo by Adam Mørk

4 - Dokk1 – Photos by Jens Marcus Lindhe / Adam Mørk

5 - Dokk1 – Photos by Jens Marcus Lindhe / Adam Mørk

6 - State Library Victoria – Photo by Trevor Mein

7 - Dordrecht - House of the City and Region – Schmidt Hammer Lassen

8 - University of Bristol Library – Schmidt Hammer Lassen + Hawkins\Brown