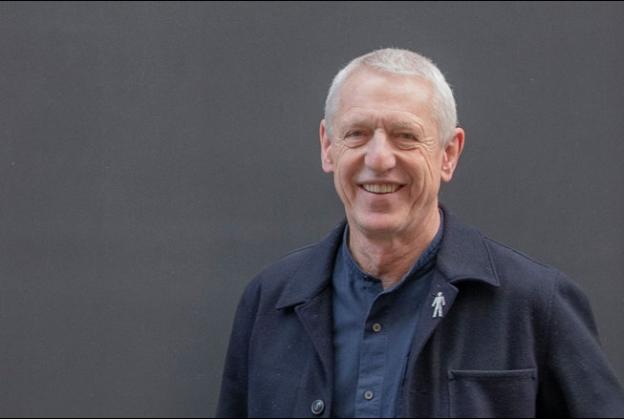

Rasmus Astrup - Partner and Design Principal, SLA

This month we’re delighted to speak to Rasmus Astrup, Partner and Design Principal in the highly innovative Danish urban design and landscape architecture practice, SLA (TenderStream members since early 2018). Based in Copenhagen, Aarhus and Oslo, its multidisciplinary team includes not only designers, but biologists and gardeners to help it tackle some of the most challenging environments in the world.

According to Rasmus, SLA brings ‘a lot of its own DNA to each project, wherever it is in the world, but also takes a lot of new inspiration and experience home to Scandinavia’. From creating a catalogue of native Middle Eastern flora and fauna able to survive arid desert conditions (no such reference book existed previously), to greening polluted and industrialised urban centres and creating rooftop ski parks, the practice puts nature centre stage to create responsive solutions for each unique location.

Read on to find out more about some of the outstanding work SLA has created in Paris, Detroit, Dubai and Scandinavia. Rasmus also shares with us his vision for his own urban garden in Copenhagen (formerly an office car park)….

As a practice, you’ve worked on some very impressive and imaginative projects, both at home in Denmark and internationally. Taking one example, Ordener-Poissonniers in Paris is a 5-hectare railway site in the 18th arrondissement regeneration zone. Your new urban ecosystem, ‘Jardin Mécano’, couldn’t be more in contrast to such a heavily industrialised location. How have you made the two aspects work together symbiotically?

Right now, there is a great demand for biodiverse and sustainable urban development, both in Paris and globally. Thus, our nature-based design pushes this agenda even further by creating new urban ecosystems in industrialised locations such as Ordener-Poissonniers.

It’s a mixed-use development and public space design project that turns the area into a carbon neutral ‘ecosystem neighbourhood’ based on nature-focused design solutions, strengthened social cohesion and on-site renewable energy production. What is especially amazing about the project is that it preserves the site’s remarkable industrial heritage while adding an abundance of green nature-centric public spaces and carbon neutral architecture.

What, ultimately, will the project be like?

The heart of the neighbourhood will be a series of connected green public spaces with outdoor restaurants, amphitheatres, band stands, and a large public garden of more than one hectare of natural amenities. The public spaces thus reinterpret the traditional Paris cityscape and strengthen the values and the qualities of the original railway site. As such they reuse its central atmospheres, materialities, topologies and elements such as railway tracks, a trolley ferry trench, railway signals and other industrial remains to create a distinct and unique urban quality specific to the site.

It will be become a vibrant urban space with 1,000 new residents, big public parks, offices, theatre, public school, industrial design incubators, a graduate school of design, food courts and urban farming - all in the heart of Paris. Thus, the Ordener-Poissonniers project will act as a generous green gift to the city.

By combining the strong industrial character with innovative designs and public ecosystem services, we create a new standard for nature in Paris - where it is everywhere and where humans, plants and animals can live and flourish together. The project is developed in close collaboration with building architects Biecher Architectes for Emerige and OGIC.

And what is your own favourite aspect about the project?

The thing I love the most about the Ordener-Poissonniers project is that all is designed to make biodiversity, natural amenities, sustainability and post-industrial heritage the starting point of the entire development. A truly radical way of literally growing a new neighborhood out of the existing Parisian soil that will increase quality of life for every Parisian.

Also in Paris, SLA’s Ternes-Villiers project won the international mega-competition ‘Reinvent Paris’. Your design comprises a 5,500 sqm urban roof deck spanning the congested Boulevard Périphérique. Were there particular challenges regarding the choice of planting in such a polluted urban setting? And what can you tell us about the tea plantation - we’re intrigued!

The great challenges of our global polluted cities lie on a city and political level: 422,000 people in Europe die every year because of air pollution. We must act on this, simple as that. Paris now has an ambitious biodiversity plan, which hopefully will inspire and establish requirements for its future development. More cities should learn from that.

Anyway, in our Reinvent Paris-project, the plants have an air cleaning-function. More than 200 different tree and plant species are implemented. All the trees are local from the Paris region and are chosen in terms of how they perform in relation to cleaning air and obtaining rainwater, as well as the site-specific wind, sun, and shadow conditions. 90 percent of the roof is covered by greenery, including the tea plantation, which the project’s café will harvest to make fresh tea all year round.

The project thus combines city nature-based ecosystem services, fully climate-adapted urban spaces and new social meeting places with underground parking, pedestrian-friendly connections and large roof terraces. The high level of greenery transforms the project into an ‘air-cleaning machine’, where plants and trees not only improve air quality but reduce the heat island effect and increase the area’s biodiversity.

The project not only offers green attractions at street level, but lifts urban life and city nature high over Paris’ facades and roofs, which adds a whole new dimension to what it means to live and work in Paris. The project is developed in close collaboration with building architects Ferrier Marchetti Studio and Chartier Dalix for BNP Paribas Real Estate.

Moving on to Copenhagen, we find your Amager Bakke rooftop park with its sports and leisure amenities, rock-scapes and some 300 new pine and willow trees. The design even incorporates a ski slope involving the use of a very steeply pitched roof. What challenges did such a topography present in terms of the landscaping?

Creating an activity-filled nature park on the rooftop of an 88-metre high waste-to-energy plant (designed by our friends from BIG and ARC) is a project that has not been done before. The steep slope of the roof put great demands on the planting design and the construction of the landscape, and the complicated wind and weather conditions of being high up created difficult living conditions for trees and plants. The heat from the large energy boilers under the roof also had to be handled, and a variety of security and safety demands addressed.

To solve these challenges, we worked with a wide range of nature-based design solutions, testing types of vegetation and materials in 1:1 experiments, designing new steel ‘tree-beds’ to fix the trees into the sloping roof, finding new ways of in-situ casting the concrete blocks, and so on.

Lastly, all plants, trees and biotopes have been specially selected from local species to accommodate the challenging living conditions of the roof and to provide optimal microclimate and wind shelter for the visitors. The aim is to make Amager Bakke a truly public rooftop park with a strong aesthetic and sensuous city nature that gives value for all Copenhageners and all visitors - all year round. Now, Amager Bakke becomes home to birds, bees, butterflies and flowers, creating a vibrant green pocket and forming a completely new urban ecosystem for the city.

Danish newspaper ‘Politiken’ gave Amager Bakke six out of six hearts in its 2019 review. What did they like about it so much, and how did it make the SLA team feel to receive such recognition for the project?

First of all, Amager Bakke is truly unique in its vision and design. The reviewer in Politiken described the project as one of the ‘wildest and most fantastic ideas in the 2010s architecture’. The sensory nature-based design of the park is simply not something you expect on a waste-to-energy plant.

The reviewer, Karsten R F Ifversen, says that Amager Bakke is a new way of being present in a city. For the first time ever, citizens can now be in close contact with the industrial energy production - in a cool and recreational way. Amager Bakke is thus a new landmark and a new way of developing not just industrial infrastructure, but also cities.

The whole SLA-team is very happy to have overcome the challenges and created something never seen before in modern architecture. It has been an amazing multidisciplinary team effort both internally and with our fantastic collaborators. You should really come hiking, skiing, climbing or just enjoying the new nature on the roof of Amager Bakke anytime - it is a truly unique nature experience.

Staying in Copenhagen, can you tell us a little about the SUND Nature Park? What difference do you think it has made to the students and locals who frequent it?

Today, the modern campus is different to the traditional and closed campuses that used to be built decades ago. The new SUND is an open and holistic campus that gives a lot back to the surrounding city - and becomes part of the city. SLA has created the nature park around the iconic Mærsk-building, designed by our great collaborator, building architects C.F. Møller. The inspiration for the landscape was found in the history of the location and its unique atmosphere. Now, our design of the nature park ensures that students, employees and citizens can walk or bike across the city area, which thereby connects the city in a whole new way.

The Panum Institute (SUND) is an educational institution with a long history and tradition as well as a modern research centre with thousands of daily users. Here, we wanted to create a lush and recreative park and urban space, where everyone can relax, enjoy the city nature and hang out all year round - and they simply love the nature park, which is so fantastic to see every time I bike by it.

The new characteristic landscape and SUND Nature Park consists of varied mini-biotopes with a diverse range of plant species, creating a peaceful green pocket, which actually survived one of the warmest summers in Danish history in 2018.

Outside Europe, SLA is currently involved in the regeneration of the US city of Detroit. Can you tell us what you’re working on, and what you’re seeking to achieve there?

Our Monroe Blocks in Detroit - developed with building architects Schmidt Hammer Lassen, Neumann Smith and Buro Happold - is a 18,800 square metre project, where we at SLA have designed the landscape and urban space. Our ambition with the project is to create a city that is not connected by car mobility, but where the human scale is the starting point.

Monroe Blocks will be an icon for the future development of the city. It will affect much more than the project area, setting the agenda the surroundings and context.

The project re-establishes the historic alleyways and introduces new public spaces and green areas in the city. We are embracing the local nature and materiality by using new and native vegetation as well as local clay, which emphasises each of the urban spaces’ unique identities and characters while adding human scale, social values and a local identity. This results in a greener, cleaner and more pleasant urban environment for a vibrant contemporary city life.

And how have you managed to create green environments in the highly urbanised, rainwater-poor city of Dubai?

Yes, actually we work both in Dubai and Abu Dhabi. Our presence in the Middle East is founded in a desire to create open, biodiverse and informal public urban spaces where people meet eye to eye - no matter background, nationality or income. Because we believe that every nation’s culture is based on its nature. Thus, the key is to adapt to the local context and carefully choose trees and plants that will live perfectly in the heat and sun without much rainwater.

But in order to do so, you need great local knowledge, which we could not get anywhere when we started working in the Middle East. So, what to do when there are no publications and information on the local flora and fauna? We collect all the data and publish a book about the local plants, trees and animal life ourselves. Of course, nothing less... In this way, we have a deep knowledge and insight on the Middle East ecosystems, which we now use actively in all our nature-based designs of parks, buildings, et cetera, in the region.

This knowledge helps us use local plants and soil as well intelligent watering systems in all projects, which reduce the water consumption by up to 50 percent in contrast to conventional landscape architecture. Furthermore, we can reduce the temperature by up to 10 degrees in a project when working intelligently with wind and shading.

Are there any other exciting projects you’d like to share with us – past, present or future?

Oh yes, many! But to highlight one then, our transformed roundabout ‘Sankt Kjelds Square and Bryggervangen’ in Copenhagen is innovation, biodiversity and climate adaption all combined. Here we have blended cloudburst adaption with recreational urban spaces and planted 580 new trees to enhance the area’s biodiversity. The locals enjoy the new urban space, where they can take a rest with the feeling of lying in a forest - in the heart of Copenhagen.

Another project we are very proud of is our Novo Nordisk Nature Park that brings the qualities of nature and storm water management into the corporate world, so the employees can go for a walk during meetings or during breaks. It enhances the mental health of the employees by being amongst nature. This is also brought close to the building, so the employees get a natural feeling inside their offices - increasing efficiency and life quality for everyone.

I think Novo Nordisk was one of the first projects that really introduced ‘New Nature’ typology. It was the first large scale project in Denmark with 100 percent storm water balance (even for the heaviest rains) and a serious biodiversity content. The tree nurseries had to deliver trees in natural shapes, and we implemented dead trees in the planting for insects, moss and mushrooms. We had to change Novo Nordisk’s very professional maintenance system, since there were not any manuals describing how to maintain ‘nature’ - it became a paradigm shift for us, the client and others.

What would you say SLA’s core philosophy is? What, as a practice, do you aim to contribute to the world?

At SLA we use nature to solve some of today’s hardest urban challenges while providing genuine life quality for all. This is our core philosophy. Nature is thus the focal point of everything we develop, draw and think.

Architecture, masterplanning, urban spaces and landscapes are just some of the means that we use to put nature's processes into play. What distinguishes us from our colleagues is our fundamental nature-based approach that nature’s grown environment and the built environment differ from one another. Although they are not comparable, they are complementary. And to us, they together constitute a holistic architecture.

At SLA we also emphasise the personal qualities of ethic and integrity. And we know that we can be demanding to work with. Because it is not easy to make changes that are sustainable, biodiverse, robust and aesthetically meaningful. We therefore aim to challenge our surroundings at least as much as we challenge ourselves in order to create new city nature in our future societies.

On a more personal level, when, where and how did your passion for both architecture and the natural environment begin? Who first taught you all about plants?

The passion for nature, plants and architecture derives from my parents’ home and garden. I grew up in a collective, so social aspects and sustainability have been part of my life since childhood. During my childhood and when I grew up, I always loved to work physically and create things in my parents’ garden, which was full of lush plants and fresh vegetables. And actually, my mom still lives from the vegetables in her garden, which is a great inspiration to me.

However, one day during my teenage years I browsed through the book about the different educations and universities to choose from after high school, because I wanted to study something that I could see myself, interests and values in. I had a hard time choosing between architecture and landscape architecture - but ended up choosing landscape architecture. Nonetheless, I am very fortunate as I now get to work with both architecture and landscape architecture at SLA every day.

I gained great knowledge about plants during my studies, but because of our multidisciplinary approach at SLA with both biologists, gardeners and other experts as colleagues, I now learn something new all the time. Thus, my passion for both architecture, the natural environment and plants never ends - it continuously develops.

And lastly, what is your own garden like at home?

I just moved to a new house in Copenhagen that is located at one of the most polluted and noisy streets in the city. So, my family and I have exactly the same challenges as our Reinvent Paris-project at the Boulevard Périphérique. Our ‘garden’ is still a parking space of concrete as the previous owners used the house for offices. My plan is to transform the parking space into a small and wild urban habitat that contributes and enhances the city’s biodiversity while cleaning the air and harvesting the stormwater - like our work at SLA. It is thus fantastic to solve - or at least contribute to solving - some of our urban challenges through my own private garden, both aesthetically and functionally.

Interview: Gail Taylor