Dorte Mandrup

Exemplary projects reveal the power of design to create positive change

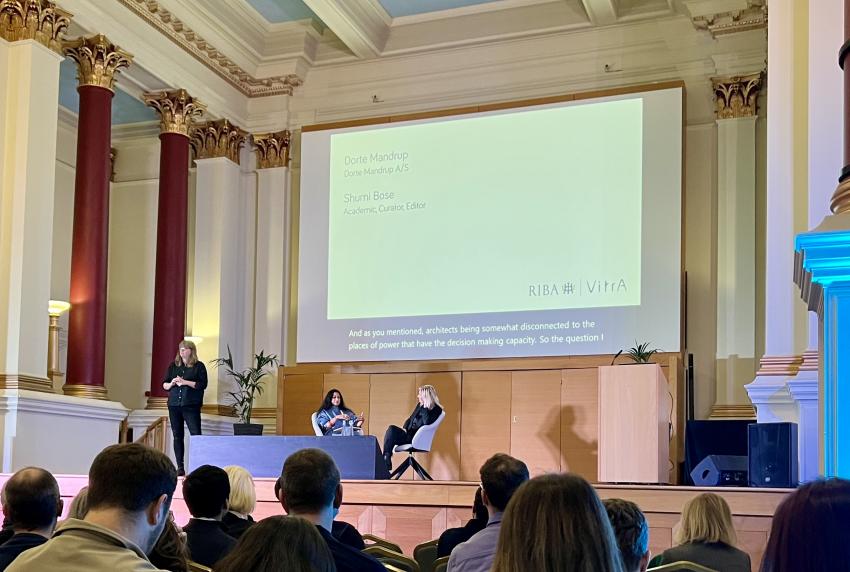

In December, Tenderstream member Dorte Mandrup gave an illuminating and inspiring keynote speech at BMA House as part of The RIBA + VitrA Talks Programme, exploring the power of design to create positive change in communities. The programme theme, Building Empathy: Design for our Time, highlighted the role of architects in shaping environments that are accessible, meaningful, and responsive to the people who use them.

Dorte presented six key projects that exemplify her layered, context-driven approach, many of which are situated in challenging natural environments and demonstrate that an architect should work with a site’s unique characteristics rather than challenge them by imposing their vision. The discussion that followed the talk, led by Shumi Bose, Senior Lecturer in Architecture at UAL Central Saint Martins, examined the difficulties that architects face when attempting a nuanced approach that prioritises social value and sustainability, while working within the economic and political environment of our time.

Dorte introduced each project with a clear explanation of the natural, historical, and cultural context of its location, revealing how careful research and study inspired the resulting designs.

For the Ilulissat Icefjord Centre in Greenland, the challenge was to add a structure to an area almost defined by a lack of human presence that would offer residents, tourists, and climate researchers the ultimate vantage point from which to observe the immense amount of ice produced by the Sermeq Kujalleq glacier. Cultural sensitivity was necessary to avoid introducing ideas drawn from vernacular architecture, such as the igloo, that might be associated with ice in the popular imagination but are not characteristic of the area. The resulting building instead takes its cue from nomadic structures, offering shelter while appearing transitory, and exerting a light touch on the landscape.

Currently under construction, The Whale features an iconic design that blends into its surroundings in Andenes, on the Island of Andoya, Norway. As with the Icefjord centre, the structure's purpose is to celebrate nature, so it should not work against it. Initiated by the local community, with the state stepping in later to assist, the project utilises an ex-military station to promote sustainable tourism that teaches visitors about ocean life, motivating them to protect it. Situated 300km north of the Arctic Circle, Andoya is located next to a deep ocean trench, making it a perfect place for whale-watching. The design rises as a soft hill on the rocky shore, while the curved roof becomes a new vantage point, inviting visitors and locals to walk upon it. Inside, a large, column-free room follows the site's topography.

Another challenge is adapting an existing building to make it more responsive to its surroundings. The Wadden Sea Centre in Ribe, Denmark, hosts an exhibition that takes visitors on a journey through the surrounding World Heritage status landscape as experienced by the area's millions of migratory birds. Expanding on an existing structure dating from 1995, Dorte took inspiration from the shape of Viking longhouses, which would have been constructed like islands in the lowland landscape. Local craft traditions were utilised to construct the centre’s thatched roof and façade, which emerge organically from the flat terrain.

Another contemporary use of historic tradition is exemplified by the residential craft college in Herning, where the methods used to build the structure are intended to inspire the students as they embark on their careers, working on their own projects and alongside established professionals. Situated in a growing town on a horizontal wetland, the college features Nordic timber and reused brick, creating a protective space that stands out as a shelter, while seeming natural.

Two contrasting projects drew on dense urban environments and their layered histories. The Centre for Health in Copenhagen is situated next to a nursing home complex, built in the 19th century to provide a calming, self-contained village atmosphere. The new centre is constructed from a series of timber frames with aluminium cladding, forming a simple, inviting structure with a warm and open interior, establishing a welcoming atmosphere for people who might feel anxious about their health and taking the steps necessary to improve it.

With a very different function, Dorte’s design for the Exile Museum in Berlin, which is yet to be constructed, incorporates the ruins of Anhalter Bahnhof. This busy station was at the heart of creative 1920s Berlin, before becoming a departure point for those fleeing the country following the rise of Nazism. Between the historic fragment and the new museum, a void will open to commemorate what is lost. At the same time, a dramatic three-storey foyer will give give visitors a sense of travel, sloping upwards towards the museum spaces and evoking the feeling of embarking on a daunting yet significant journey.

In the discussion following the talk, and in the audience questions, Dorte and Shumi noted that although respect for a building’s surroundings and its impact on the environment should be a given, different countries have very different approaches, with methods changing according to the political climate. The difficulty is reaching consensus on what sustainability means in practice and how it should be measured.

On the question of how much agency and influence architects might have, Dorte noted that as clients do not necessarily follow best practices and are subject to economic pressures, political intervention is necessary to create regulations to enforce standards. When incorporating methods that may seem expensive, such as traditional crafts, testing and research must be conducted to demonstrate their effectiveness. Solutions should be scalable, and not just gimmicks used to generate headlines for a particular project.

Dorte stated that she felt architects should stand for certain values and questioned the idea that working for clients with directly opposing values can, in a roundabout way, introduce progressive ideas. Shumi noted that her students, conscious of actions that might be necessary to combat social and environmental change, are inspired by Dorte’s stance, which demonstrates a clear-sighted consideration of the natural world and the local communities impacted by architectural developments.

When introducing the RIBA + Vitra Programme, Kate Dooley, Exhibitions and Programmes Curator at RIBA, stated: “At a time of social and environmental uncertainty, we must spotlight those driving architecture forward with empathy and purpose.” During this talk, held in the warmth of the BMA hall, sheltered against the cold winter weather outside, it felt significant to listen to a discussion that touched on the headwinds against progress currently taking place across the world. Dorte’s designs, often situated in difficult environments, offer a light in the darkness and a shelter from which to appreciate nature. As humans, we need to protect ourselves from the environment which could harm us, without destroying that environment, which, as well as challenging us, also sustains us and makes our existence possible.

Lucy Nordberg

Tenderstream Head of Research

Start your free trial here or email our team directly at customerservices@tenderstream.com